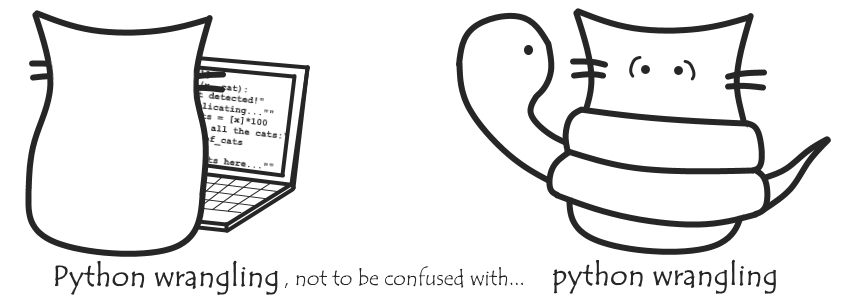

Welcome back to another fun round of Python-wrangling (a.k.a. what I’ve learnt to do with Python during GSoC)! Today I’ll be talking about ‘private’ variables and the property attribute.

If you’re not familiar with Python but want to follow along, you could have a look back at the brief notes I made back here, or go check out a (proper) tutorial.

‘Private’ and ‘public’ in Python

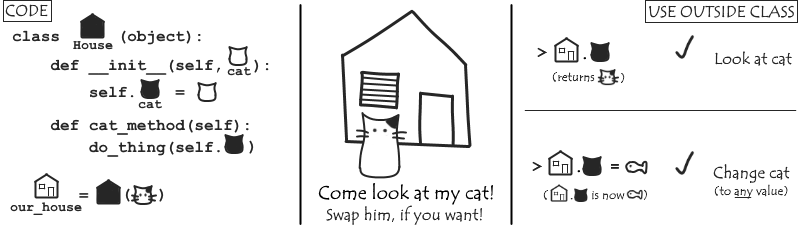

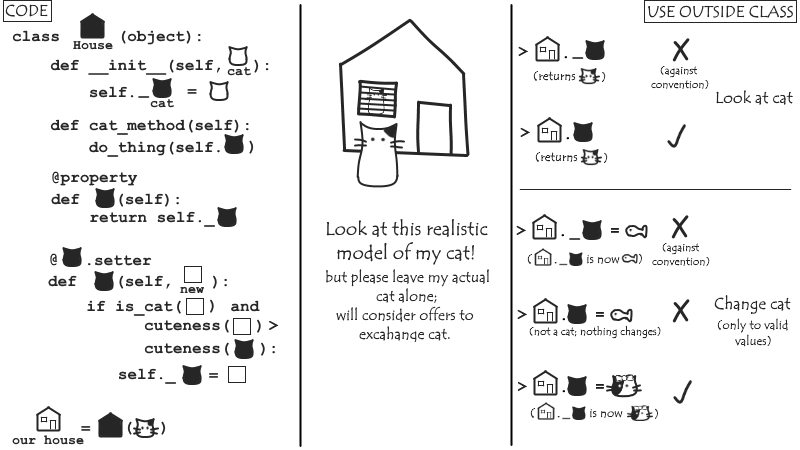

Let’s say we have a House class. For many instances of House – including (of course) ours – it’ll have a cat attribute. Within House, we can interact with the cat as self.cat, so we can define the necessary methods for looking after them (feed, clean, worship, feed again…). But the cat is also accessible from outside the house (as house_instance.cat): this means anyone could come along and look at or, heaven forbid, swap our cat with something else – even something non-feline! A house’s cat is ‘public’, where we might prefer they be ‘private’.

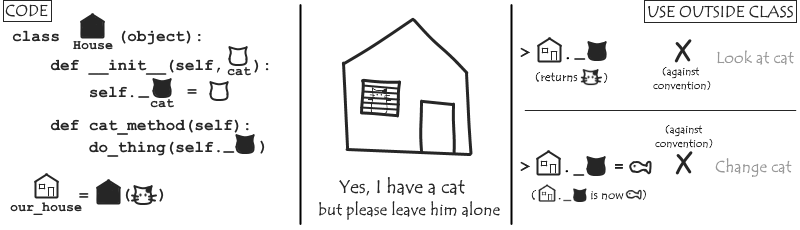

Many programming languages have ways of declaring variables as ‘private’ (more or less, which things can’t be used outside of the current bit of code). In Python, ‘private’ variables don’t strictly exist. Instead, we follow a convention: if we name something beginning with an underscore (say, _cat), we’re indicating that object shouldn’t be considered public and so shouldn’t be used outside of e.g. the class it’s an attribute of. People can still technically access and change our cat through our_house._cat, but we’re politely asking them not to.

(The use of underscores isn’t just for when we don’t want people to mess with attributes, it can also be for things which don’t really serve a direct purpose to the user – say, a method that performs an intermediate step, and so isn’t useful by itself. By including the leading underscore, we can indicate to a user that they need not worry about this bit of the code, and it simplifies documentation. There are also a couple other uses for leading and trailing underscores in Python – you could see more about that in here.)

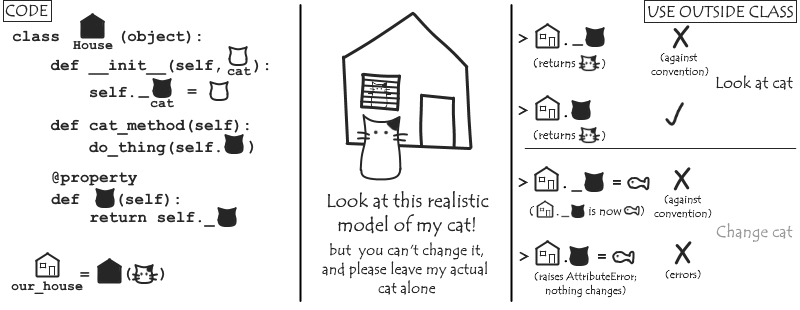

But what if we decide we do want people to see our cat? (He is, after all, the very best cat). What we can do is make a property attribute, cat, that returns the value of _cat when we want its value but will throw an error if we try set it. We can do this using @property, the property decorator.

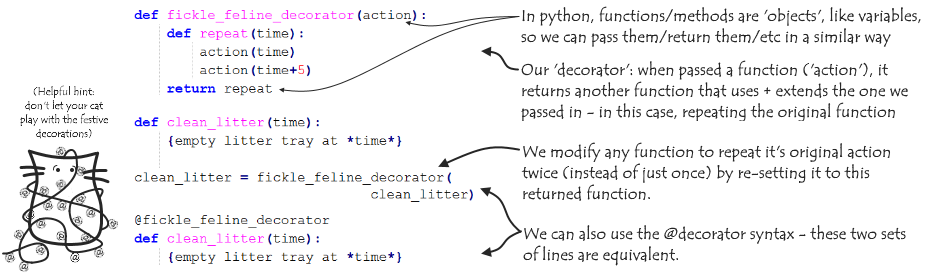

A tangent on decorators

There may arise situations when using Python where we might want to ‘modify’ a bunch of functions/methods in the same way. For example, say we’ve programmed our Python friend to take care of several cat-related chores at certain times; but as any cat owner knows, as soon as you do something for your cat, you’re probably going to need to do it again pretty soon.

We want to modify all the cat-caring actions so instead of performing them just once at the specified time, there’s a five minute delay then the action is performed a second time. To do this, we’ll use a decorator.

property is a built-in decorator in Python that we can apply to a ‘getter’ method (and optionally, additional ‘setter’ and ‘deleter’ methods – more on these below) to get a property attribute which, instead of having a stored value like other attributes, will return the result of the ‘getter’ method when it’s value is asked for. Above, we’re using a simple ‘getter’ that just returns the value of another attribute, but we could have something that say, returns something different depending on values of other attributes, or calculates a new value - see some of the examples below.

Conditional setting

Back to our House/cat situation: we’ve prevented anyone being able to come along and swap our cat for a fish, but what if we did want to let people change him, so long as we can control what he’s changed to? Obviously, we still want a cat, and let’s say we’ll also only accept the change if the proposed new cat is cuter than our current one. Having used @property to create a cat property, we can now add a ‘setter’ for cat using @cat.setter. Now, rather than throwing an error when we try house_instance.cat = new_value, this ‘setter’ method will be run; depending on new_value, there may or may not be any change.

We could similarly use @cat.deleter to specify a ‘deleter’ to run when we use del(cat) - for example, when we move house we can use this to both remove the _cat attribute and perform clean-up tasks like removing all the cat hair or uninstalling the cat door.

Some practical examples

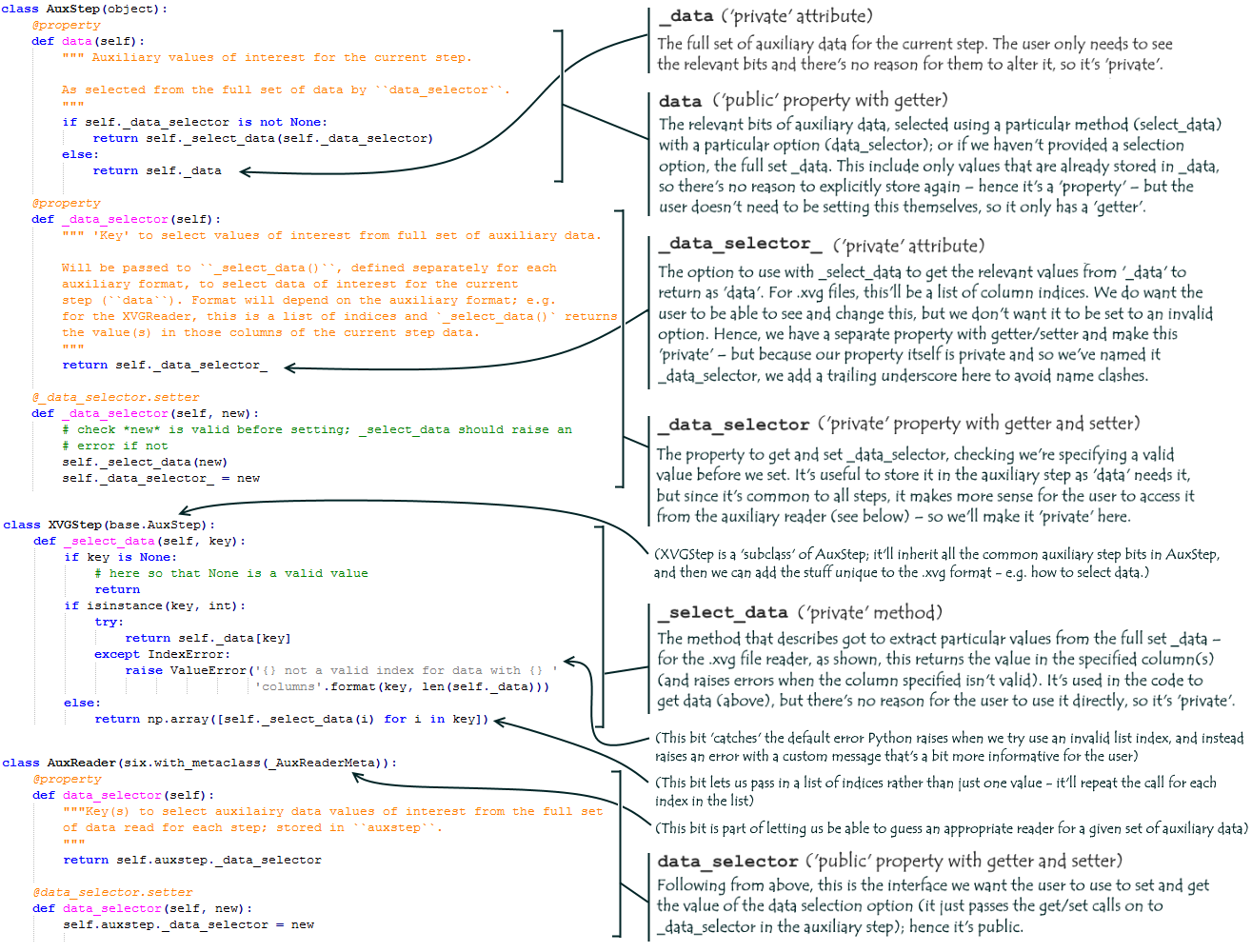

On the more practical side of things, here’s some snippets showing how I’ve been using getters, setters and ‘private’ attributes in varoius ways for my GoSC project, namely the ‘add_auxiliary’ part. Again, you can go see the full version on GitHub.

Some brief background - the main interface when reading auxiliary data is the auxiliary reader class (there will be different reader classes for different auxiliary formats, but they all inherit from AuxReader, where all the common bits are defined); the reader has an auxstep attribute which is an ‘auxiliary step’, which stores the data and time for each step (again, there are different auxiliary step classes for different formats, with AuxStep having the common bits).

And that’s a brief rundown of private vs. public and properties in Python - I hope you found that fun and informative!

See you next time!