While working with trajectories these past weeks, I’ve been reading up and making use of a neat set of things related to the iterator protocol in Python. Iterators are what let us loop over each frame in a trajectory in turn, analysing as we go, and so are a key part of what I’m doing with my ‘add_auxiliary’ subproject and of MDAnalysis in general! Let’s take a look.

Iterators and Iterables

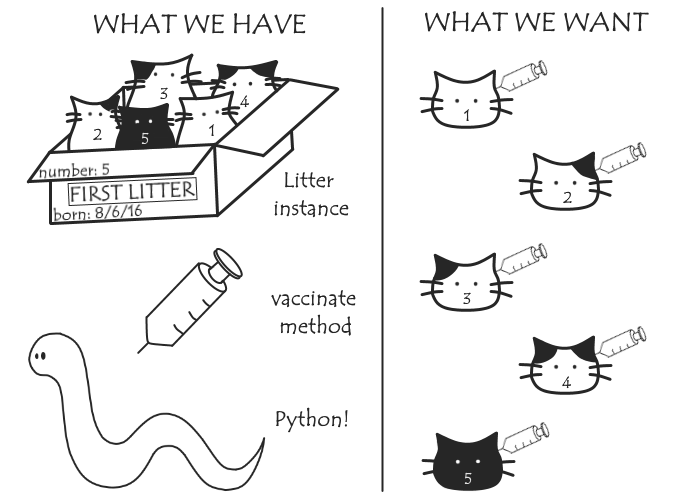

Let’s imagine our cat has been a busy boy, and we’ve ended up with a bundle of little kittens to deal with. Now it’s time for vaccinations, and while we could ourselves pull each kitten out one by one, vaccinating each in turn, we know what a potential health hazard that is. Instead, we’re going to get our good friend Python to do it for us!

You might already know in about for loops in Python. Basically, if we have:

for variable in sequence:

do_something(variable)

what will happen is that, first, variable is set to the ‘first item’ in sequence, and do_something run with that value. variable is then set to the ‘second item’ in sequence and do_something run again, and so on until we’ve run do_something for every item in sequence.

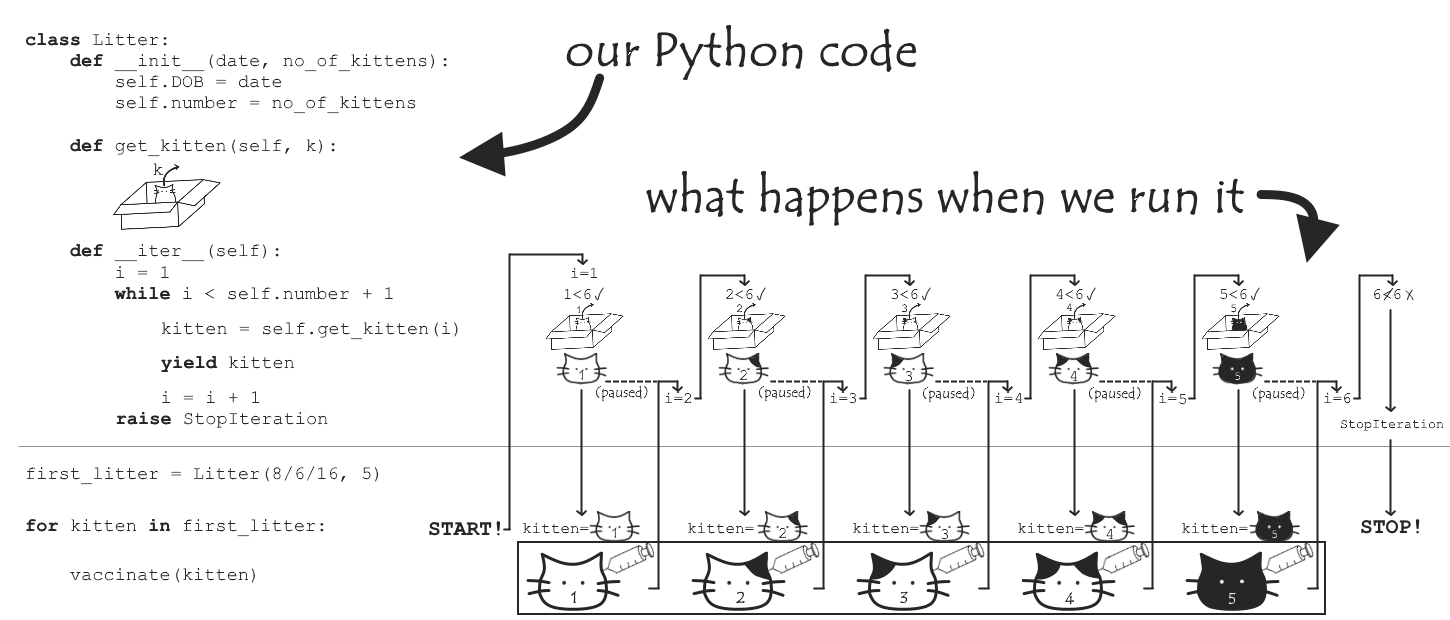

We want sequence to represent the litter, do_something to be ‘vaccinate kitten’, and variable to be set to each kitten in turn. If we represent the litter as simply a list of kittens, we don’t need to do anything further – the process of determining ‘first item’, ‘second item’ for lists (as for several other data types) is pre-built into Python, and follows each item in the list as you’d expect. However, it would be nice if we had a Litter class (of which this first_litter is an instance) so we could store both our kittens and things like a date of birth and the total number of kittens, and have a nice framework to use if the event of any future litters.

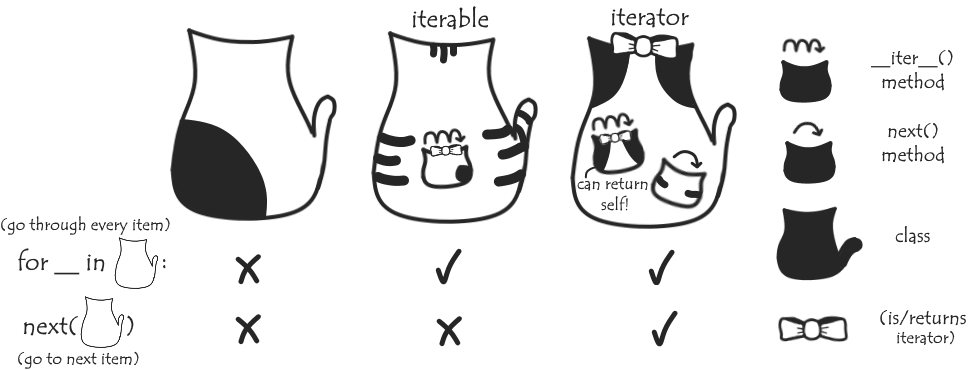

We need to tell Python how to determine each of the items (kittens) that belong to first_litter. We can do this by defining some special methods in the Litter class to make it iterable or (more specifically) an iterator:

-

an iterable class has an

__iter__()method -

an iterator needs an

__iter__()method and anext()(or__next__()in Python 3) method

__iter__() needs to return an iterator object, so when the class is itself an iterator, __iter__() can just return self. The next() method needs to return the ‘next’ item in the class each time it is called, and raise a StopIteration error if we’re trying to move past the last item. When we run a for loop, next() is used to get the value of each item in turn, and the loop exits when it gets StopIteration instead.

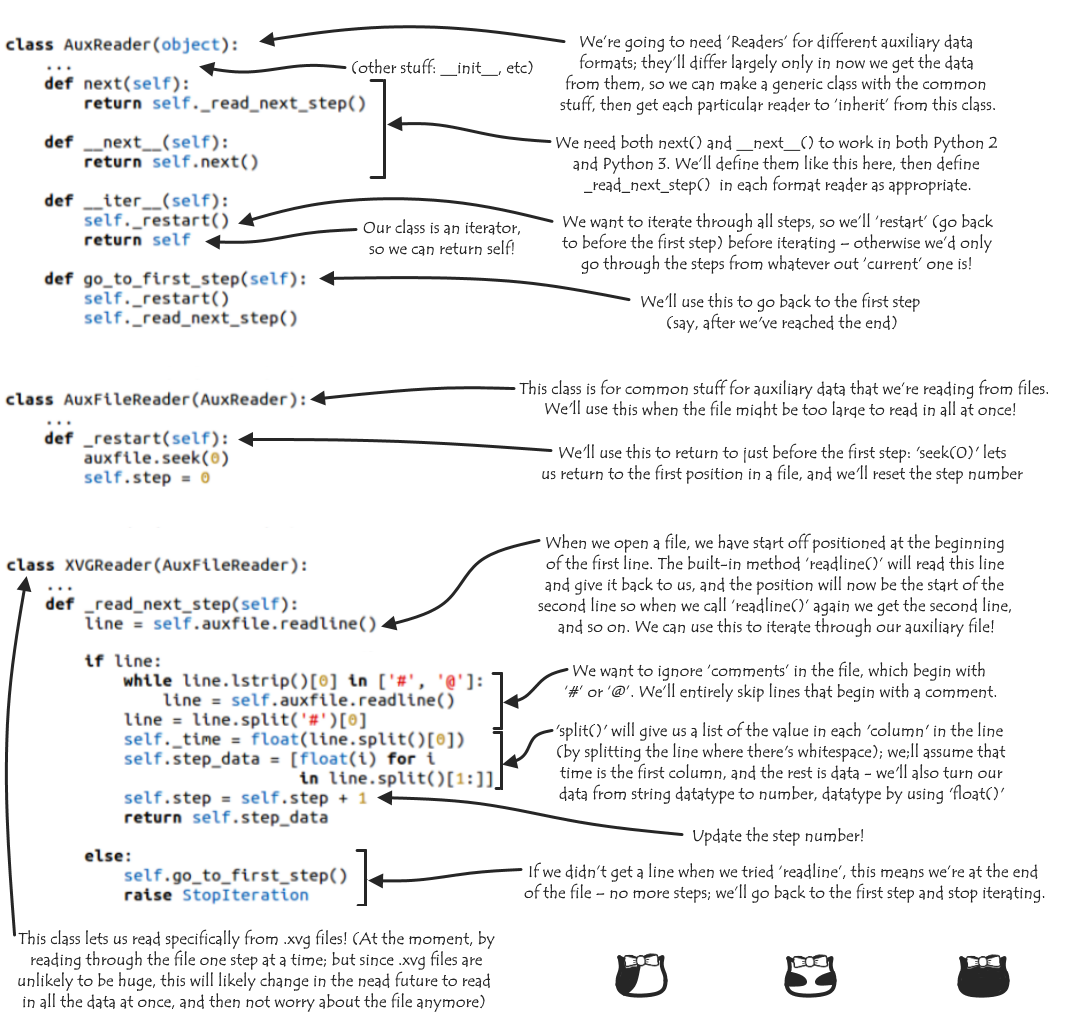

The XVGReader class I’ve included below, which forms part of my ‘add_auxiliary’ subproject, is an example of a custom class that is an iterator. For now, we’re going to make our Litter class iterable instead. To do this, we need to make __iter__() return an iterator; we can do this by making it a generator function.

Generators

A generator function returns a generator, a type of iterator. We make a generator function by adding a yield statement to it, where we might otherwise use return. What happens is that, when first called, the function will run until the first yield statement is reached, at which point the appropriate value is returned (this will be out ‘first item’) and the function ‘pauses’. When, at some point later, we’re ready for the next value, the generator is resumed (e.g. by calling it’s next() method), and progress continues until yield is encountered again; the new value (the ‘second item’) is returned, the generator pauses, and so on. After we’ve gone through the final yield and reach the end of the function, it’ll raise the StopIteration error.

So how does this look for our cats?

And now we’ve successfully vaccinated all out kittens, without endangering our personal safety!

A more practical example: XVGReader

Unfortunately, I’m not being paid to play with kittens all summer, so before I go I’ll leave you with some excerpts (for reading auxiliary data stored in the .xvg file format) of what I’ve been working on to show how I’ve actually been using Python’s iteration protocol. Until next time!