Nearly two weeks of coding down, about eleven to go! It’s been a bit of a slow start, but now I’m starting to get into the swing of things. This post was originally going to be longer, but I’ve decided to split it, so unfortunately you don’t get as many cats this week. On the plus side, the intended second half – the inaugural What I Learnt about Python This Week (witty alternative name pending) – should be up in the next couple of days, rather than the usual 1+ week!

I’ll even give you a sneak preview:

What I will be doing in this post is expanding more on my plans for the first part of my project – adding auxiliary files to a trajectory. I’ll start with a very brief overview of some bits of Python, intended only to try and help the following make a bit more sense if you’ve never used it or programmed before. If you want to actually learn how to use Python, go check out one of the numerous tutorials!

Some brief notes about Python

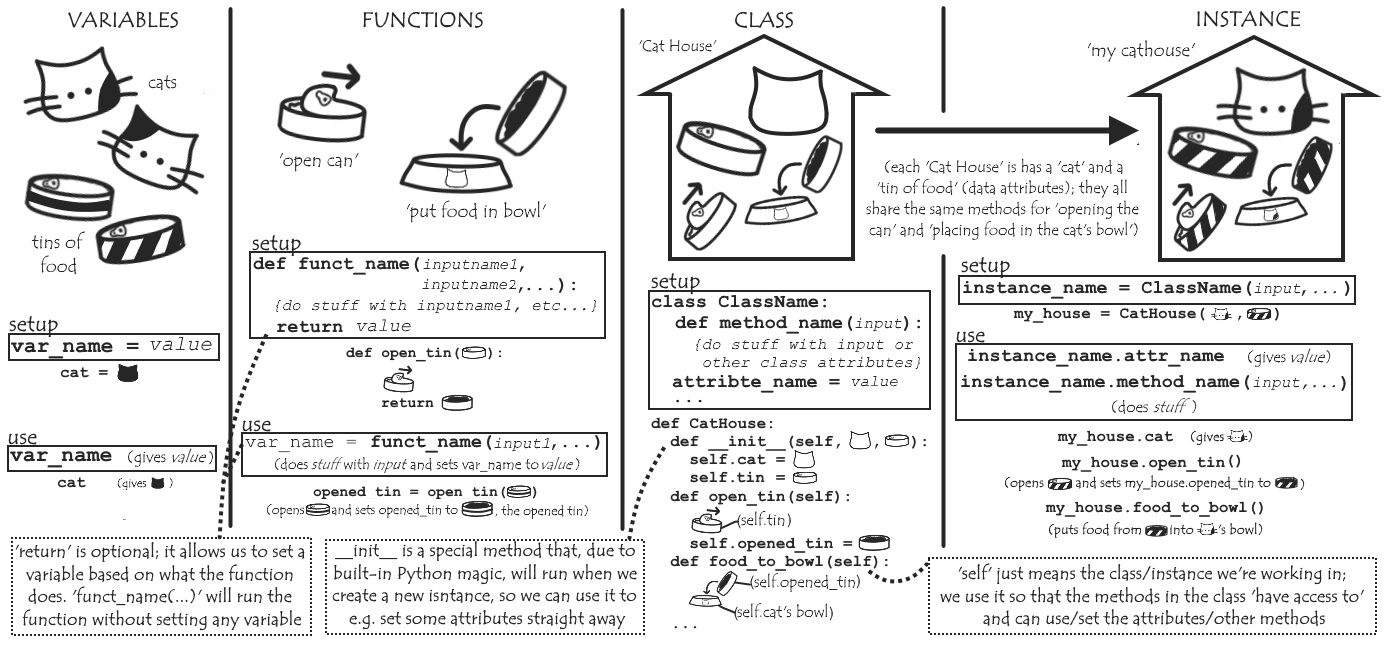

In Python, we store data in variables. Depending what it is, the value we store will have a particular data type: common built-in examples are numbers, strings (a sequence of characters), and lists (a sequence of values, each can have a different datatype).

Functions are things that (usually) take some input and do something with it.

A class is essentially a framework/container used to store a bunch of related variables (attributes) and functions (also attributes, more sepcifically methods) which can use or alter the data attributes. We can create different instances of a class, each with a particular set of attribute values; this allows us to keep track of different related set of values, and to more easily work with them using the accompanying methods.

The Way Things Are

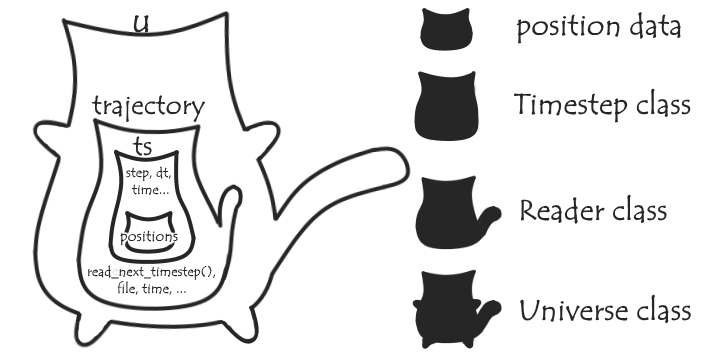

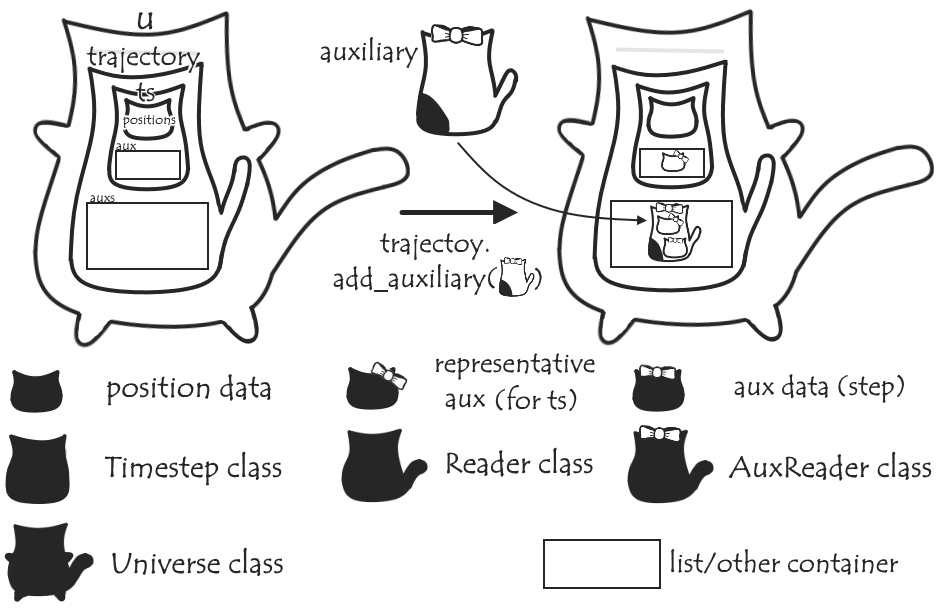

In MDAnalysis, working with a simulation trajectory goes something like this: we make u, an instance of the Universe class, to contain information about our system, including the attribute trajectory. trajectory is itself an instance of a Reader class; there are several different Readers, each able to reach trajectory data from a particular file format.

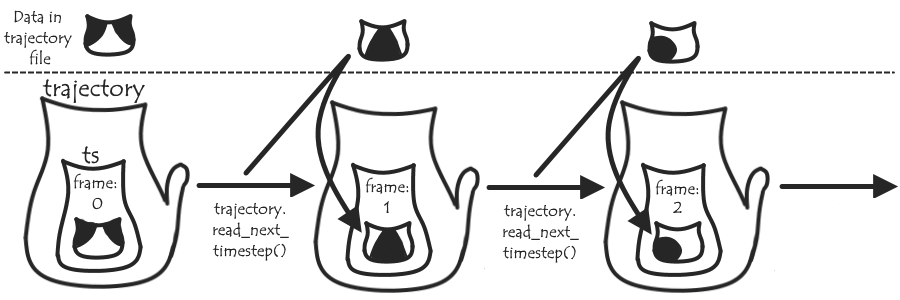

trajectory stores general information – like the name of the file where the trajectory data is written, and the time between each recorded timestep (dt) – as well as frame and ts, respectively a number identifying a particular timestep (numbering sequentially from 0) and an instance of a Timestep class which stores the position (and velocity and forces, if available) data from that frame.

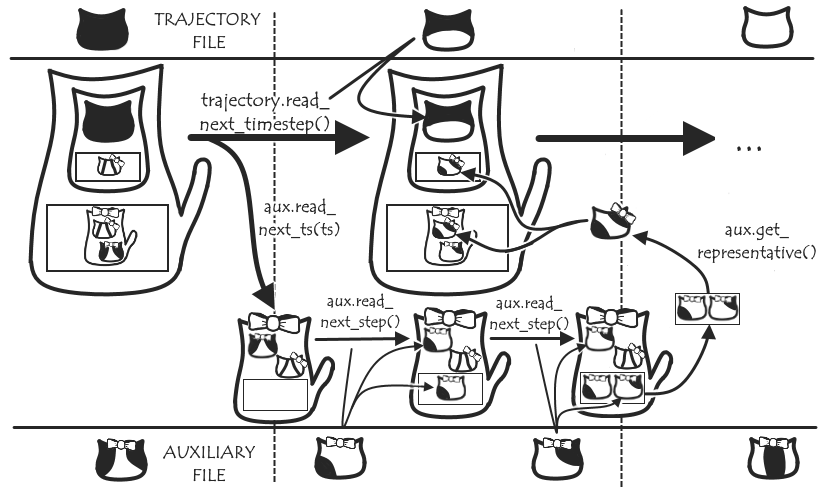

The trajectory reader has a read_next_timestep() method that (as per the name) can be used to read the next timestep recorded in the trajectory file, and update the frame number and ts with the appropriate values.

This allows us to perform particular analyses along the whole trajectory by looping through each frame in turn, updating the data in ts as we go - which is very useful! What ‘add_auxiliary’ is trying to achieve is to allow us to perform anaylsis with both the position data and other sets of data not stored in the trajectory file (i.e. ‘auxiliary’ data), while running through this loop.

The Way Things Will Be

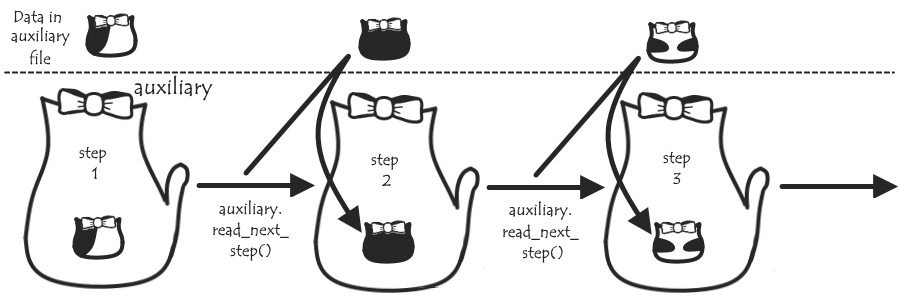

Basically, we want ts to store, in addition to the position data of the current frame from the trajectory file, auxiliary data recorded elsewhere. First, we’ll need some AuxReader classes that will work in a similar way to the trajectory Readers: each instance will store some general stuff like a name of an auxiliary file, a step number, and the value of the auxiliary data for that step (step_data). A read_next_step() method will allow us to update step and step_data as appropriate.

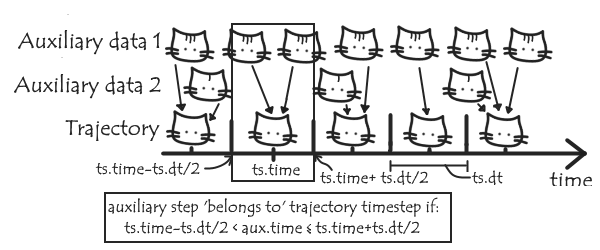

These steps may not, however, match up with the trajectory time steps (there are several reasons why we might want to record the auxiliary data say, twice as often). First, we can assign each auxiliary step to its closest trajectory timestep:

We can now add another method, read_next_ts(), that’ll use this condition and read_next_step() to read through all the auxiliary steps belonging to the next trajectory timestep, keeping a record of the auxiliary values from each of these in a ts_data list. We’ll also have a get_representative() method that will based on this list pick a single value to represent the timestep – we’ll let the user choose if this is, say, an average, or the value from the closest step, and store this representative value, ts_rep, in the AuxReader. For convenience, we’ll also copy this value to ts, to be stored in ts.aux under a custom name.

To the trajectory Reader, we’ll add an auxs list (initially empty), and an add_auxiliary method that will, given a set of auxiliary data, make the appropriate AuxReader instance and add this to the auxs list. Out data structure now looks something like this:

Lastly, we’ll also add a couple of lines so that when we want to read the next timestep, in addition to running read_next_timestep() on the trajectory, we’ll run read_next_ts() on each auxiliary reader in auxs. This all means that when we move to the next timestep, both the position and representative auxiliary data in ts will be updated, and we should now be able to analyse them alongside each other!

There’s a bunch more stuff I’ve skipped over that gives us more options and neatens up the process (I’ll be talking about some of this in the next post, so stay tuned!), but hopefully for now you have a clearer idea of what I’m currently doing. As it stands, I have the framework I’ve discussed here up and (mostly) working, for the test case of auxiliary data stored in the ‘.xvg’ file format; so I’m mostly double checking everything works as I expect, looking at expanding to more general auxiliary readers and seeing what additional user-control can be added. I now have a work-in-progress pull request, so head over there to see the nitty-gritty code details and/or pitch in with any ideas, feedback or advice; and I’ll see you again soon with Post 3.5!