With the GoSC coding period now started, here’s that background and for my project I promised last post! I’ve tried to start from the (relative) basics so the context of what I’m trying achieve with my project is more clear; if you already know how Molecular Dynamics and Umbrella Sampling work (or you’re just not that interested), feel free to skip ahead to the overview of my GoSC project or projected timeline.

So what is MD?

Experimental approaches to biochemistry can tell us a lot about the function and interactions of biologically relevant molecules on larger scales, but sometimes we want to know the exact details – the atomic scale interactions – that drive these processes. You can imagine it’s quite difficult experimentally to see and follow what’s going on at this scale!

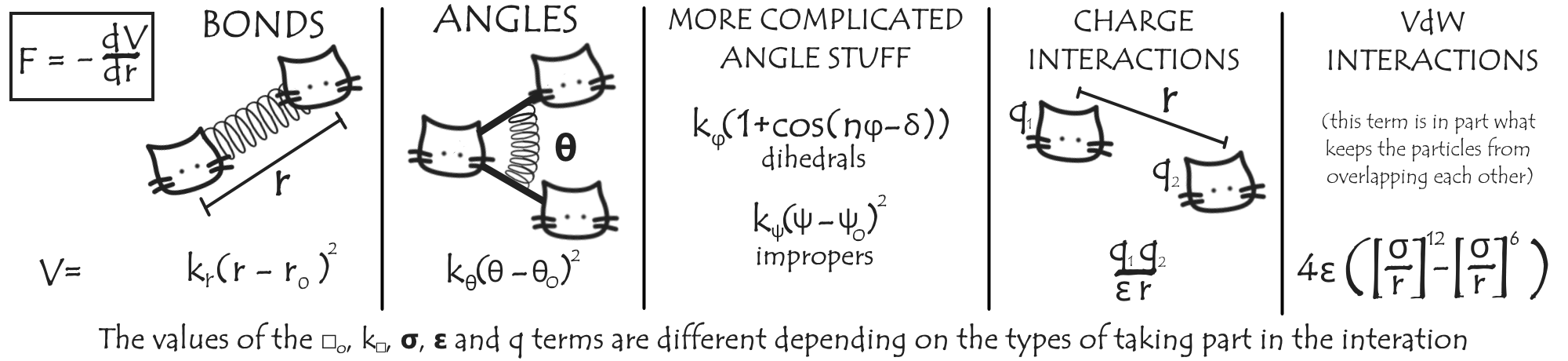

This is where Molecular Dynamics, or MD, comes in. What we do is use a computer to model our system – say, a particular protein and its surrounding environment (usually water and ions) – on this scale and simulate how it behaves. To make our simulations feasible, we make some approximations when considering how the atoms interact: in general, they are simply modelled as a spheres connected by springs to represent molecular bonds, with additional forces to represent e.g. charge interactions.

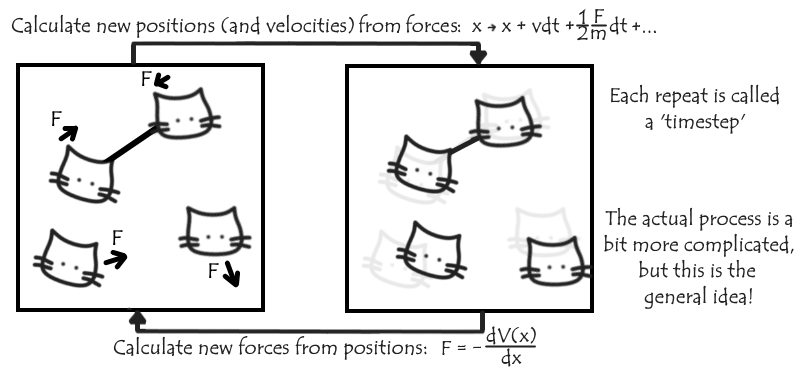

The set of parameters that describe these interactions form a ‘force field’ and are chosen to best replicate various experimental and other results. Using this force field, we can add up the total force on each atom due to the relative location of the remaining atoms. We make the approximation that this force is approximately constant over the next small length of time dt, which allows us (given also each particle’s velocity) to calculate how far and in which direction they’ll move over that time period. We move all our particles appropriately, and repeat the process.

The force isn’t really constant, so for our simulations to be accurate this dt needs to be very small, typically on the order of a femtosecond (a millionth of a billionth of a second!), and we need to iterate many, many times before we approach the nanosecond or greater timescales relevant for the events we’re interested in.

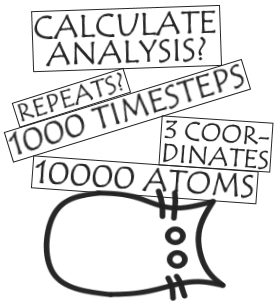

It would not be feasible to keep a record of every single position we calculate for every single timestep. Even when our output record of the simulation – the trajectory – is updated at a much lower frequency, a typical simulation may still end up with coordinates (and possibly velocities and forces) for each of tens of thousands of atoms in each of thousands of timesteps – it’s quite easy to get buried in all that data!

This is where tools like MDAnalysis help out – by making it easier to read through and manipulate these trajectories, isolating atom selections of interest and performing analysis over the recorded timesteps (known as frames).

If you want to know more about Molecular Dynamics, particularly the more technical aspects, you could head over to the Wikipedia page or read one of the many review articles, such as this one by Adcock and McCammon.

But what do umbrellas have to do with anything?

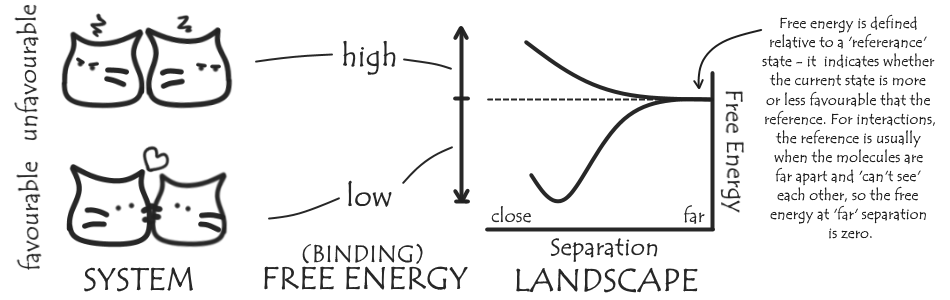

Sometimes we want to know more about our system than ‘molecule A and molecule B spend a lot of time together’ – we want to quantify how much molecule A likes molecule B, by calculating a free energy for the interaction. The lower the free energy of an interaction or particular conformation of our system, the more favoured it is. We can also talk about free energy landscapes which show how the free energy of our system changes as we vary part of it, for example bringing two molecules together.

Say you want to figure out which toys your cat likes the best. You can wait and see where he spends his time in relation to them, and if you watch long enough you can make a probability distribution of how likely you are to find your cat at any place at a point in time. This probability will correlate with how much he favours each toy, and so we can calculate from the probability distribution the free energy of cat-toy interactions.

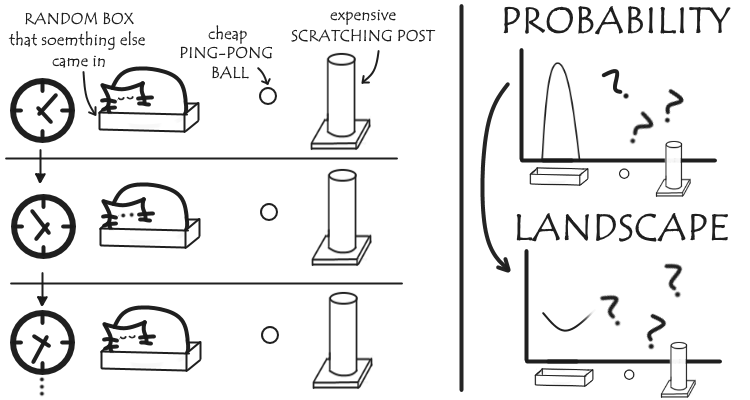

The problem is, you might be watching for a long time.

The same is true in biochemistry. If a particular interaction is very favourable, we’re not likely to see the molecules separate within the timeframe of our MD simulation: without some sort of reference state, we can’t calculate our free energy, and we never see any less-favourable states that might exist.

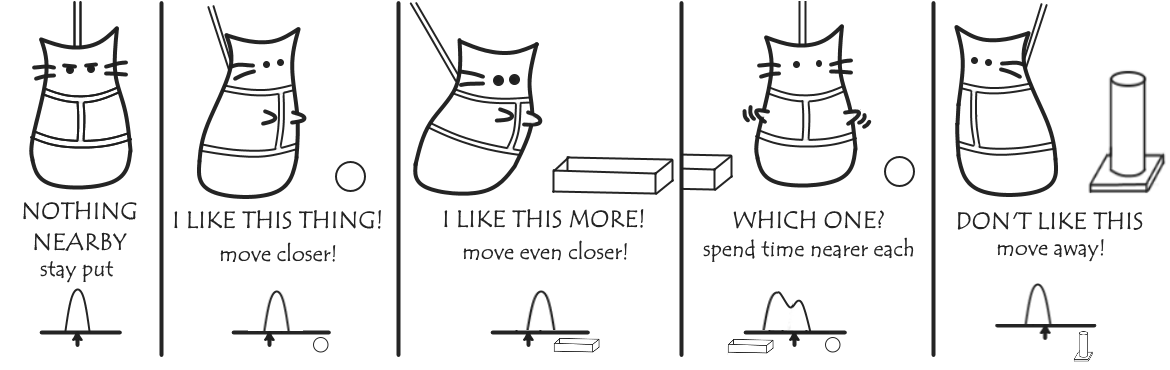

Instead, what we do it put out cat on a lead to force him to stay near various locations. There’s still a bit of give in the lead, so for each location we restrain him, he’ll still shift towards the things he likes, and away from the things he doesn’t.

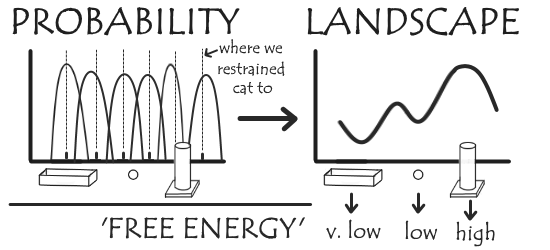

Combining the probability distribution from each these we get a much more complete (though biased) probability distribution than before. These can be unbiased to get our free energy landscape, and from this we can determine the most favoured toy: it’ll be the one corresponding to the lowest free energy.

(Naturally, it’s the random box.)

(Naturally, it’s the random box.)

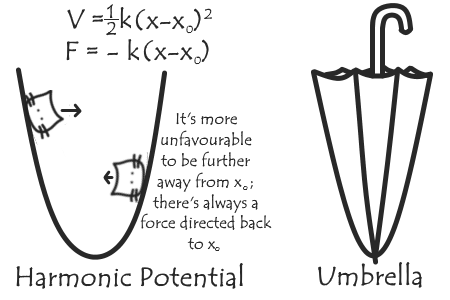

This is more or less the Umbrella Sampling (US) method. To be a little more technical, we determine the free energy between two states (such as two molecules interacting or separate; a ‘binding’ free energy) by first picking a reaction coordinate that will allow us to move from one state to the other (e.g. distance between the two molecules). We then perform a series of MD simulations (or windows) with the system restrained at various points along the reaction coordinate by adding an additional term to the force field, usually a harmonic potential - the shape of which gives the name ‘umbrella’ sampling.

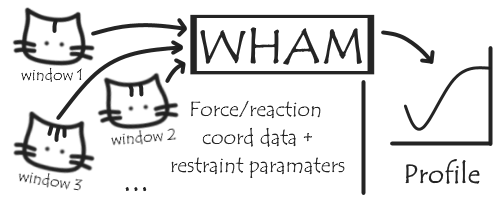

The probability distributions are calculated by recordng the value of the reaction coordinate (or, equivilantly, force due to the harmonic potential) during each window, and unbiased and combined using an algorithm such as WHAM (I’ll be talking about this in more detail in the future!). The free energy landscape along the reaction coordinate we get out is called a Potential of Mean Force (PMF) profile.

Again, if you’re interested in reading more, you could try the Wikipedia page, the original US article by Torrie and Valleau or the read up on WHAM.

So what am I doing for GoSC?

Currently, MDAnalysis doesn’t have tools for dealing particularly with US simulations, both in terms of specific analysis (including WHAM) and handling the trajectories and associated extra data from each window. I’m hoping to make this a reality.

My project is currently divided into three main parts. Below is a brief overview for now; I’ll talk more about each as I encounter them and form a clearer picture of how they’ll play out. Each is associated with an issue on the MDAnalysis GitHub page, linked below, so you can pop over there for more discussion there.

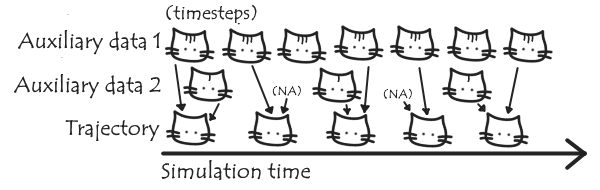

- Adding auxiliary files to trajectories. Usually when performing US simulations, the value of the reaction coordinate/force is recorded at a higher frequency than the full set of coordinates stored in the trajectory. Being able to add this or other auxiliary data to a trajectory, and dealing getting the data aligned when they’re saved at different frequencies, will be generally useful to MDAnalysis (not just for US). See the issue on GitHub here.

- An implementation of WHAM, perhaps a wrapper for an existing implementation, so WHAM analysis can be performed from within MDAnalysis. See the issue here

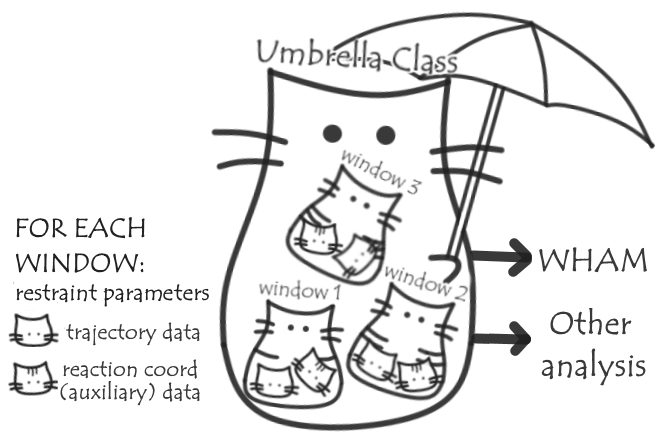

- An umbrella class, to deal with the trajectories for each window, loading the auxiliary reaction coordinate/force data, and storing other relevant information about the simulations such as the restraining potentials used; passing the relevant information on to run WHAM and allowing other useful analysis, such as calculating sampling or averages of other properties of the system in each window or as a function of the reaction coordinate. Read the issue here.

Timeline

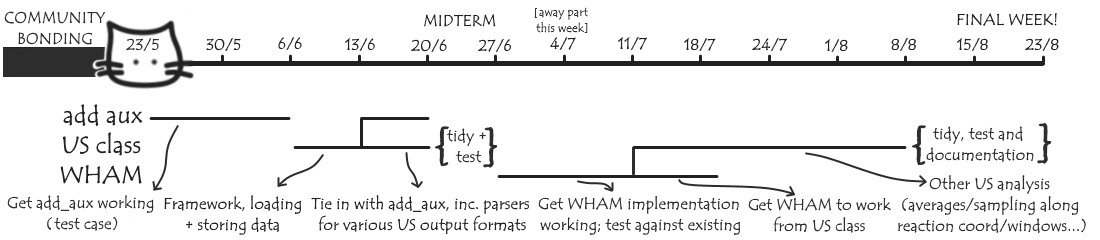

Here’s my current projected timeline for dealing with these three tasks:

This is likely to change as I encounter new ideas and issues along the way, but hopefully by mid-August I’ll have something nice for dealing with US simulations in MDAnalysis to show off!

Phew, well that ended up being a monster of a post - worry not, I don’t expect any posts for the immediate future to be this long!

I’ll be back soon, with more on the adding-auxiliary-data part of this project and how my first week has gone. I’m currently experimenting with the design on this blog, and writing an ‘About’ page and a proper ‘Home’ page, so watch out for those, and see you again soon!